View from the Other Side: Proponents of Prosecution

Three "responsible voices" in favour of the prosecution of Assange were recently aired on the ABC (Australia's state funded broadcaster). That truly painful podcast is analysed here.

PARTS 1-8 of this series have presented information about the life and work of Julian Assange that rarely appears in the legacy media, as an historic and educational counterweight to the very superficial and pro-prosecution narrative that generally appears there.

However, as a kind of early birthday present for Julian Assange, a programme purporting to seriously examine the ethical and legal underpinnings of the case against Julian Assange was shared with the world by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC), Australia’s flagship, state funded broadcaster. Much of that podcast is preserved and analysed here as a kind of exemplar of the kind of misinformation which is spread at the “intellectual” and academic end of the legacy press spectrum.

On Thursday 23 Jun 2022 the ABC’s “The Minefield” aired a one hour podcast featuring Waleed Aly in conversation with his co-host Scott Stephens and later their guest Katharine Gelber. All three have post-graduate academic qualifications, and have held teaching positions at Australian Universities. Waleed Aly considers that each is a “responsible voice” (27:30).

Waleed Aly is an Australian academic, writer, lawyer, and broadcaster. Also a lecturer in politics at Monash University working in their Global Terrorism Research Centre, and a co-host of Network Ten's news and current affairs television program The Project.

Scott Stephens is the Online Editor of Religion and Ethics for the ABC, and a writer and editor of several books, including having edited a number of books on the Slovenian philosopher and cultural critic, Slavoj Žižek (who is a friend of Julian Assange). He has also been a university lecturer in theology and ethics, and was a speaker at Integrity20 at Griffiths University.

Katharine Gelber is the Head of the School of Political Science and International Studies, and Professor of Politics and Public Policy at the University of Queensland.

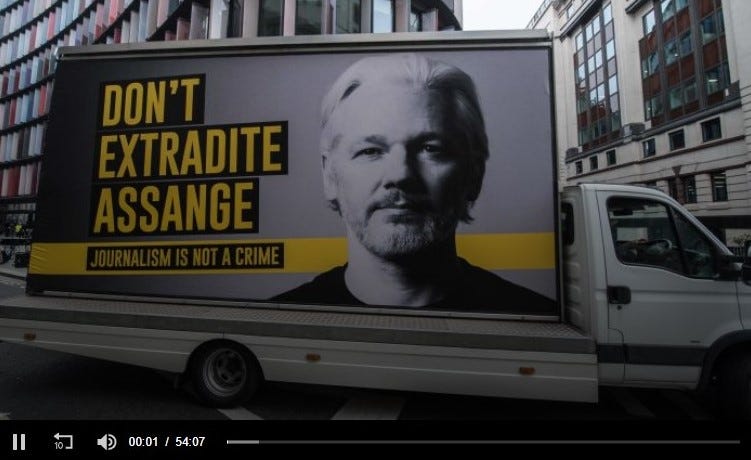

The podcast was then released on the ABC website accompanied by another image of an Assange billboard truck:

The title of this podcast between “responsible voices” was “Is Julian Assange entitled to a “free speech” defence?” and it purported to be a discussion of some of the key intellectual and ethical issues at play in the Assange case.

I listened to this arrogant (and ignorant) discussion of “questions of abstract principle" (10:15) involved in the Assange case - and report on it here so you don't need to suffer a whole hour of this self-important garbage. Of course, in saying that I have exposed myself as what these venerable academics call with contempt “an Assangist”. But you knew that already since this is PART 9 of the Julian Assange Archives series.

The podcast opens with the co-hosts, Waleed Aly and Scott Stephens laughing about the fact they they had never before done a ‘Minefield’ programme about Julian Assange. It is hard to understand how such egregious neglect of the plight of Australia’s most famous journalist could be amusing - a plight that has now gone on for more than decade, which the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention (UNWGAD) has determined is arbitrary detention, and which escalated more than three years ago to what many serious people (such as former Foreign Minister of Australia Bob Carr, in the EU parliament on 14 November 2019) call “political prisoner” status - but perhaps I am hypersensitive to slights on Assange.

The first 10 minutes or so of this podcast (published by Australia's flagship state broadcaster) is a very long string of defamatory statements dressed up as "they say", purporting to be a summary of the pro- and anti- points (although according to this presentation there are really no reliable positive points since these are all said to be a form of "Assangism"). Rather than type out a transcript of that nauseating diatribe, I present here the summary offered on the podcast webpage:

“The name “Julian Assange” excites passions and divides opinion like few others. To his supporters, he is a champion of democracy, a heroic journalist in a just cause, a fearless advocate for political accountability and transparency. Their devotion to Assange often verges on ideological or even religious fervour — what we are tempted to call “Assangism”. In some of the more extreme expressions of this devotion, his supporters strenuously deny (at least publicly) any wrongdoing, irresponsibility, recklessness, vindictiveness, pettiness, or errors of judgment in his work with WikiLeaks (much less any criminality when it comes to allegations made against him by two women in Sweden). They insist there are no grounds for any charges to be laid against him that couldn’t also be levelled at news organisation like the New York Times and the Guardian.

To his detractors and opponents, Assange is not just irresponsible but conspiratorial — prepared to receive and publish classified information, but also to solicit and assist in illegally procuring that information (most notably in the case of Chelsea Manning, the former US military analyst who, between November 2009 and May 2010, acquired and provided classified military information to WikiLeaks about war crimes in Iraq). They say he displays none of the journalistic restraint, prudence, judgment, and objectivity that are essential to the vocation of journalism, and that, at best, Assange is little more than a mediator between reputable news organisation and the real “sources”. They say, moreover, that his willingness to receive material obtained from servers of the Democratic National Committee by the Russian intelligence service — information which was then published during the 2016 presidential campaign to do maximum damage to Hillary Clinton’s candidacy — is further proof that Assange will collaborate with dangerous, anti-democratic actors if it serves his agenda.

For some, Assange’s cause is righteous, and his physical and mental wellbeing are threatened by the United States’ and UK’s ongoing prosecution/persecution; for others, Assange is distasteful, dangerously immoral (or at least amoral), anarchic, and heedless when it comes to the consequences of his decisions. The former often seems unwilling to brook any criticism of Assange; the later often seems unable to acknowledge any good to have come from his actions.”

I find it hard to see the above as any kind of balanced presentation, and the rest of the one hour podcast proceeds in much the same manner. It is my opinion that there is no attempt at all to create any kind of fair balance here. (Around the same time the ABC’s “MediaWatch” provided a much fairer picture of the various voices that have spoken about Assange.)

While the introduction purported to inform the audience of the full spectrum of views on the Assange case, it failed to canvas the views of:

The international jurists who wrote to UK authorities in support of Julian Assange, advising against his extradition [YouTube] [Text]

The international collection of doctors who have written a number of open letters urging against the extradition and in favour of his release in order to protect his health [Doctors For Assange]

The views of international journalist associations, almost all of which have stated that the US charges and any extradition endangers free press values, and the more than 2,000 journalists who have also signed the ‘Speak Up For Assange’ petition.

The various international human rights NGOs, including Amnesty International, who have called for the release and non-prosecution of Assange.

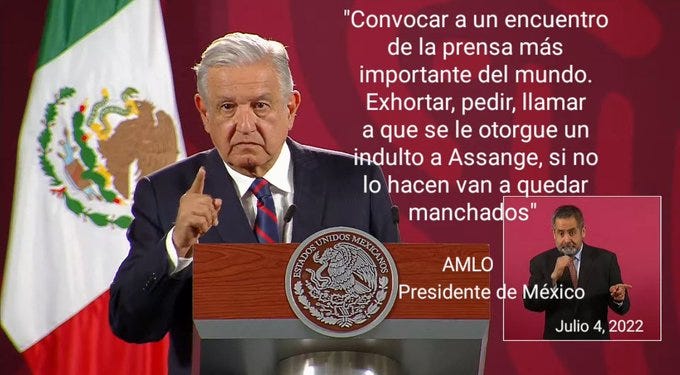

A week after the lower court verdict, Al Jazeera looked at public figures (politicians) in support of the release of Assange and found many, with more having spoken out (and even having offered asylum) since.

The reader can decide for themselves how fair or helpful this podcast was, as the rest of this analysis will present much of what was actually said, together with some of the relevant information that was simply ignored (or perhaps not known to these commentators). Journalistic sins of both commission and omission.

At 13:58 they bring up "the judicial concern for the sheer humanness of the person who is in the dock" [a concern notably absent during the extradition hearing] "that is not ancillary to ... the rule of law, but is an essential part of it".

COUNTERPOINT - The Glass Box

This might have been a good time to discuss (as Craig Murray did) the glass cage in which Assange was confined during the extradition hearings, but the moment was allowed to pass.

TRANSCRIPT CONTINUES

"The point of inalienable human dignity of the person in the dock is that it is mean to be inalienable" said one of them (at 14:37).

[I guess they didn't listen to the actual court sessions, or read Craig Murray's detailed descriptions of the unpardonable indignities to which Julian was subjected over the many months of those hearings].

COUNTERPOINT - Craig Murray “The Armoured Glass Box is an Instrument of Torture” (2 March 2020)

“In Thursday’s separate hearing on allowing Assange out of the armoured box to sit with his legal team, I witnessed directly that Baraitser’s ruling against Assange was brought by her into court BEFORE she heard defence counsel put the arguments, and delivered by her entirely unchanged.

I might start by explaining to you my position in the public gallery vis a vis the judge. All week I deliberately sat in the front, right hand seat. The gallery looks out through an armoured glass window at a height of about seven feet above the courtroom. It runs down one side of the court, and the extreme right hand end of the public gallery is above the judge’s bench, which sits below perpendicular to it. Remarkably therefore from the right hand seats of the public gallery you have an uninterrupted view of the top of the whole of the judge’s bench, and can see all the judge’s papers and computer screen.

Mark Summers QC outlined that in the case of Belousov vs Russia the European Court of Human Rights at Strasbourg ruled against the state of Russia because Belousov had been tried in a glass cage practically identical in construction and in position in court to that in which Assange now was. It hindered his participation in the trial and his free access to counsel, and deprived him of human dignity as a defendant.

Summers continued that it was normal practice for certain categories of unconvicted prisoners to be released from the dock to sit with their lawyers. The court had psychiatric reports on Assange’s extreme clinical depression, and in fact the UK Department of Justice’s best practice guide for courts stated that vulnerable people should be released to sit alongside their lawyers. Special treatment was not being requested for Assange – he was asking to be treated as any other vulnerable person.

The defence was impeded by their inability to communicate confidentially with their client during proceedings. In the next stage of trial, where witnesses were being examined, timely communication was essential. Furthermore they could only talk with him through the slit in the glass within the hearing of the private company security officers who were guarding him (it was clarified they were Serco, not Group 4 as Baraitser had said the previous day), and in the presence of microphones.

Baraitser became ill-tempered at this point and spoke with a real edge to her voice. “Who are those people behind you in the back row?” she asked Summers sarcastically – a question to which she very well knew the answer. Summers replied that they were part of the defence legal team. Baraitser said that Assange could contact them if he had a point to pass on. Summers replied that there was an aisle and a low wall between the glass box and their position, and all Assange could see over the wall was the top of the back of their heads. Baraitser said she had seen Assange call out. Summers said yelling across the courtroom was neither confidential nor satisfactory.

I have now been advised it is definitely an offence to publish the picture of Julian in his glass box, even though I didn’t take it and it is absolutely all over the internet. Also worth noting that I am back home in my own country, Scotland, where my blog is based, and neither is within the jurisdiction of the English court. But I am anxious not to give them any excuse to ban me from the court hearing, so I have removed it but you can see it here.

This is the photo taken illegally (not by me) of Assange in the court. If you look carefully, you can see there is a passageway and a low wooden wall between him and the back row of lawyers. You can see one of the two Serco prison officers guarding him inside the box.

Baraitser said Assange could pass notes, and she had witnessed notes being passed by him. Summers replied that the court officers had now banned the passing of notes. Baraitser said they could take this up with Serco, it was a matter for the prison authorities.

Summers asserted that, contrary to Baraitser’s statement the previous day, she did indeed have jurisdiction on the matter of releasing Assange from the dock. Baraitser intervened to say that she now accepted that. Summers then said that he had produced a number of authorities to show that Baraitser had also been wrong to say that to be in custody could only mean to be in the dock. You could be in custody anywhere within the precincts of the court, or indeed outside. Baraitser became very annoyed by this and stated she had only said that delivery to the custody of the court must equal delivery to the dock.

To which Summers replied memorably, now very cross “Well, that’s wrong too, and has been wrong these last eight years.”

Drawing argument to a close, Baraitser gave her judgement on this issue. Now the interesting thing is this, and I am a direct eyewitness. She read out her judgement, which was several pages long and handwritten. She had brought it with her into court in a bundle, and she made no amendments to it. She had written out her judgement before she heard Mark Summers speak at all.

Her key points were that Assange was able to communicate to his lawyers by shouting out from the box. She had seen him pass notes. She was willing to adjourn the court at any time for Assange to go down with his lawyers for discussions in the cells, and if that extended the length of the hearing from three to six weeks, it could take as long as required.

Baraitser stated that none of the psychiatric reports she had before her stated that it was necessary for Assange to leave the armoured dock. As none of the psychiarists had been asked that question – and very probably none knew anything about courtroom layout – that is scarcely surprising

I have been wondering why it is so essential to the British government to keep Assange in that box, unable to hear proceedings or instruct his lawyers in reaction to evidence, even when counsel for the US Government stated they had no objection to Assange sitting in the well of the court.

The answer lies in the psychiatric assessment of Assange given to the court by the extremely distinguished Professor Michael Kopelman (who is familiar to everyone who has read Murder in Samarkand):

“Mr Assange shows virtually all the risk factors which researchers from Oxford

have described in prisoners who either suicide or make lethal attempts. … I

am as confident as a psychiatrist can ever be that, if extradition to the United

States were to become imminent, Mr Assange would find a way of suiciding.”The fact that Kopelman does not, as Baraitser said, specifically state that the armoured glass box is bad for Assange reflects nothing other than the fact he was not asked that question. Any human being with the slightest decency would be able to draw the inference. Baraitser’s narrow point that no psychiatrist had specifically stated he should be released from the armoured box is breathtakingly callous, dishonest and inhumane. Almost certainly no psychiatrist had conceived she would determine on enforcing such torture.

So why is Baraitser doing it?

I believe that the Hannibal Lecter style confinement of Assange, this intellectual computer geek, which has no rational basis at all, is a deliberate attempt to drive Julian to suicide.”

[From Craig Murray (2 March (2020)]

TRANSCRIPT CONTINUES

At 15:37 (that's 25% of the conversation gone) they note that "we haven't yet gone through any of the facts", but agree that the ethical underpinning of a promised potted history should be that

"the indiscriminate application of the principles of law are paramount here …".

[Tell that to the judge who called Assange a "narcissist" after he had done nothing but state his name and date of birth.]

" … and that the distastefulness or the sanctity of the person at the heart of it ought to be given only secondary concern".

Scott Stephens then embarks (from 16:46) on a diatribe about the ways that Assange lawyers and supporters (and/or some commentators) have discussed the case amount to "pulling down people's faith in the very principles of law on which a just outcome relies".

He concludes his damning indictment of the "corrupting influence" (18:38) of such people with:

"Is the defence really worth the price of causing people to lose faith altogether in legal systems, in the internal accountability structures within journalism, of the ability of politicians and judges to behave and to act and to legislate in good faith?"

[Actually, I would have thought that if there are good reasons to lose faith in those things - and my extensive archives show there is - then it is of paramount importance that such a defence should be mounted and heard.]

[We have now reached 19:50 (one third of the way through the podcast) without a single "fact" about the Assange case being mentioned.]

Waleed Aly then asks Scott Stephens (19:50):

"What do you think Assange is on trial for?"

[Of course he is not on trial for anything - yet - as the UK case is only to determine whether he can be extradited to the US to stand trial.]

Scott Stephens cites the three US indictments (without mentioning that the third was only served up when the UK hearings were part way through).

COUNTERPOINT - The three US Indictments

The US lodged three indictments against Julian Assange. The original indictment [DOJ Indictment], for which he was arrested on 11 April 2019, was dated 6 March 2018.

On 24 Feb 2020, when the hearings began, the second indictment, dated 23 May 2019 and labelled the first superseding indictment) [DOJ Statement] [DOJ Indictment], had been lodged with the court.

Assange was not rearrested on the third indictment, dated 24 June 2020 and labelled the second superseding indictment [DOJ Statement] [DOJ Indictment], until the hearings resumed on 7 September 2020 - ie after the UK prosecutors representing the US had seen the outline of the defence argument and heard four days of their opening gambits.

This was a definite shifting of the goal posts while the game was in mid-play, and might in itself amount to an abuse of process.

TRANSCRIPT CONTINUES

Scott Stephens says (from 20:00) the US DOJ have been quite clear that Assange is not charged with receiving or publishing classified documents, but rather for:

"soliciting/conspiring with persons who had access to classified information to assist them in procurring that information - in other words 'hacking' ..." (20:31)

[and for]"publishing information ... they distinguish between the publication of redacted documents, in the public interest [aka NYT etc], versus the mass publication of documents that placed persons who were informants, especially in Afghanistan and Iraq, in immediate threat of reprisal, of imprisonment, and of death."

COUNTERPOINT - What’s with the evidence re the “conspiracy” and “hacking” charge?

There are actually two elements to this.

The first suggests that Julian Assange conspired with Bradley (now Chelsea) Manning to hack into the US system. In 2019 Chelsea Manning was subpoenaed to appear before the grand jury (in preparation for the Assange extradition hearings), and spend many months in solitary confinement (for “contempt of court”) for refusing to cooperate with their attempts to get her to give testimony on this topic. She was also fined for every day she was there. After a suicide attempt, the DOJ gave up on trying to coerce her into such testimony.

Witnesses at the extradition hearing made it clear that Chelsea Manning was already authorised to access the information she leaked, and so required no assistance from Assange. There is a suggestion that Assange tried (with no success) to help her with a hash code to cover her tracks. An expert witness testified that this could not be related to the download of the leaked files, but was most likely related to her helping fellow soldiers download music tracks. It is not even established that the WikiLeaks person she communicated with was actually Julian Assange.The second element of the “hacking” allegations comes from the testimony of an Icelander, Sigurdur “Siggi” Thordarson, convicted there of fraud (including against WikiLeaks) and sexual abuse of children. His testimony was obtained by the FBI in return for a promise of immunity from prosecution by the FBI.

The former Foreign Minister of Iceland Ögmundur Jónasson has spoken openly about this fraudster and the conduct of the FBI (who he insisted leave Iceland), and the fraudster himself has since admitted that he lied in his testimony against Assange.

COUNTERPOINT - Did Julian Assange really fail to redact the names (etc) of persons endangered by the leaks?

This point was answered long ago by an Australian journalist who was actually present as the War Logs were being prepared for publication.

See “Mark Davis exposes "lies" about Julian Assange by the Guardian & NYT” - a Twitter Moment made up of a long thread of tweets documenting the video of Mark Davis on this topic (filmed in Sydney 8 Aug 2019 at the event "Julian Assange: the Alliance Against the US Culture of Revenge") along with appropriate links. [MOMENT]

At one point Mark Davis says:

“Every moment that Julian was there, I was there. And every moment that those journalists have since narrated in their books, articles, Four Corners appearances, about the 'enormous integrity' that they had, & the 'lack of integrity' that Julian had, I can say is A COMPLETE LIE.”

Further, Witness #7, John Goetz, a Der Spiegel journalist also present, discussed the “harm minimisation” measures used in his affidavit produced during the extradition hearing:

During the release of the Cablegate files, Julian Assange even wrote to the US government offering them the chance to comment on any cables they had good reason to believe were at risk of causing serious harm if released. They did not take him up on this offer.

TRANSCRIPT CONTINUES

Scott Stephens continues (21:51):

"In other words, the two things Assange is being indicted on are the two things that no responsible news organisation in the world would do - namely:

- [1] assist in the illegal theft of classified information, in other words to conspire for the theft of that information, and

- [2] to place persons willfully, heedlessly or recklessly at risk through the mass publication, the indiscriminate publication, of material that includes their details ..."

At this point, Scott Stephens states (22:32):

"On both fronts, in my opinion, it is right for him to be extradited, it is right for him to be placed on trial."

Any suggestion (by his lawyers or supporters) that he would not receive a fair trial in the US are said to be "ludicrous" and "offensive".

COUNTERPOINT - Unfairness in the UK legal process

Abuse of process and other breaches of Julian Assange’s human rights in the UK processes to date have been documented by many well informed people, such as:

Craig Murray has created an enormous volume of writing illustrating such abuse, collected in the compendium that constitutes PART 4 of this series.

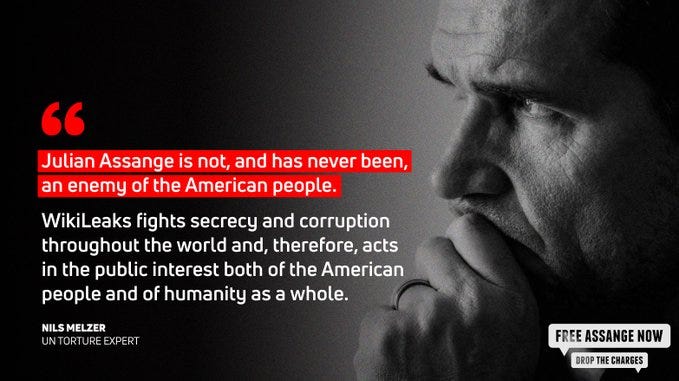

Nils Melzer, the former UN Special Rapporteur on Torture (as well as being a professor of international law) has similarly spoken out at great length on the many abuses of process inflicted on Julian Assange, accusing four different countries (UK, US, Sweden and Ecuador) of neglect of their legal obligations. Those are collected in the compendium that constitutes PART 2 of this series. His fluency in many languages (including Swedish) allowed him to peruse the original documents in multiple jurisdictions, adding credence to his findings.

Nils Melzer has also published his book “The Trial of Julian Assange” (in English, German and Swedish), so there can be little excuse for the rubbish on this topic spoken here, as one could fairly expect all responsible academics working in related fields (especially those wishing to make judgmental comments) to have read it by now.

Deepa Driver gives a one hour summary of many forms of abuse of process in “ASSANGE HEARINGS: Legal observer Deepa Driver details the anomalies” (25 May 2022) [YouTube]

Even some British MPs have now come to that point of view. Conservative MP David Davis on the imbalanced UK-US extradition treaty: "Julian Assange won't get what we think of as a fair trial in the US":

And then there are the allegations currently being litigated in a Spanish Court that the CIA spied (with video and audio) on Assange while he was in the Ecuadorian Embassy, including on his meeting with his lawyers and doctors, and with journalists and friends. Also further allegations that the CIA plotted to kidnap Assange from the Embassy, and to murder him.

This was not the only spying going on. Recently Jen Robinson, one of Assange’s lawyers settled with the UK government over illegal spying on her too.

Further, after his arrest Ecuador turned all his computer and paper materials over to the US, meaning that his accuser has access to all his legal materials. An affidavit to this affect was lodged by his solicitor during the extradition hearing, but seemingly ignored.

John Kiriakou, the US torture programme whistleblower, who spent two years in jail for bringing that information to the public, was tried (and took a plea deal) in the same Eastern District of Virginia court in which Julian Assange would be tried.

In the ABC “RN Breakfast” podcast “Assange would not get a fair trial in the US: CIA whistleblower” (28 November 2019) Kiriakou described the way that court works, and says “The chances that Julian would receive anything remotely resembling a fair trial, let alone a fair trial before a jury of his peers, it’s just nil.”

He goes on to explain the effect that having classified information discussed in a trial has on the conduct of the trial - and it doesn’t augur well for the press-friendly situation that Scott Stephens is obviously envisaging.

It is difficult to see why Scott Stephens would consider that these abuses of due process would NOT affect the fairness of the US court process, should Assange be successfully extradited. If Stephens has good cause to think that, he certainly doesn’t share them with his audience.

Further, there was a great deal of evidence given at the extradition hearings on the topic of the abusive, possibly lethal, and often illegal (see image below) conditions of imprisonment under which Julian Assange would be kept for the years it would take for his case to work its way up to the Supreme Court. Most people knowledgeable about the case expect that Assange would be dead before the case was ever resolved.

TRANSCRIPT CONTINUES

Waleed Aly (23:22) questions the grey line between "receiving" and "procuring" information and evidence from a whistleblower, especially in the case of classified information:

"… and so to talk about the journalist's role in that, and the only legitimate journalist role as purely a passive one, seems to me to create a bit of an artifice".

[...]

"Whistleblowers very often will do things contrary to the law and the people that they are working under, and if you don't have extremely good whistleblower protection laws it wouldn't necessarily make it wrong for them to do that. And I don't think it would be necessarily be wrong, in certain circumstances at least, for journalists to be assisting in that process. What we are arguing over is what the appropriate limits of that process are.Similarly with the question of publication, and what's appropriate, and the restraints on publication. [...] I do worry about the government seeking to be some kind of arbiter of that [...] because what you're arguing about now are questions of editorial judgment.”

[Good points, Waleed Aly.]

Waleed Aly goes on (25:56) to say that stories published in the mainstream press often have negative impacts on the lives of some of the parties highlighted within those stories. “There are people whose lives basically get ruined ...”

COUNTERPOINT - Lives being ruined

We have seen the long drawn out impact of people having their lives ruined by misinformation spread in the media in the recently litigated case of Amber Heard and Johnny Depp.

Very many people connected to WikiLeaks, not least Julian Assange, have suffered enormous costs in many dimensions as retaliation for their efforts in publishing truthful documents in the public interest. PART 4 of this series “The Persecution of WikiLeaks: Counting the Cost” examines many of those costs.

Waleed Aly continues (from 26:13);

"In [some] cases you'd probably have to say 'That's what happens. That's the price you pay for having a mechanism like the Fourth Estate that will publish things that people don't want published'."

There will be "collateral damage" but "there's an overriding public interest".

Mid-podcast BREAK

At this point (27:32) Waleed Aly invites Katharine Gelber to join the discussion, characterising her as a "responsible voice (that isn’t ours)".

Waleed Aly starts this section with:

“One of the central claims that has been made by way of defense of Assange, but also by way of warning about what might happen should Assange be extradited, charged formally, placed on trial, and possibly convicted, is that what’s at stake is nothing less than free speech. In other words, Assange ought to be protected, under what WikiLeaks claims is the free speech protections afforded by Article 19 of the Declaration of Human Rights, but that in the US Assange ought to be protected by the First Amendment - which most press organisations are.

Those who say that, essentially, the heavens will fall if he is extradites, say that this is a thread to journalists everywhere because its a direct frontal address on the freedom of the press. I have concerns about that line of argument, but what do you think?”

Katharine Gelber (29:07):

“So freedom of the press is a subset, if you like, of broader free speech principles. It’s a very important subset that applies to a particular type of endeavour that in current political discourse we are seeing in decline. And that is an endeavour that involves fact checking, that involves editorial judgment, that involves the ethics about disclosure where you have to balance disclosure against risk, and balance all of that against public interests.

We don’t need to talk in detail about Julian Assange’s particular case around that point, but certainly the indictment that you read out suggests that he didn’t do those things that would be associated with what you might consider to be traditional journalism.”

Scott Stephens (29:55):

“Can I just say briefly that one thing about that indictment that I did not include, and this was then the subject of the second superseding indictment is that it’s not just Assange’s particular interaction with Chelsea Manning, and a particular conspiring to achieve illegal information - in other words to assist in the act of hacking, including intervening himself to try to cover Chelsea Manning’s tracks. But also conspiring with other hackers to try to help them, to try to assist them actively, not just receiving things but to help them actively in hacking into, in breaching illegally the databases, the security walls of other organisations. So its a much more extensive rap sheet than that.”

[Scott Stephens is alluding to the testimony from the Icelander Sigurdur “Siggi” Thordarson here. See discussion above.]

Katharine Gelber (30:35):

“So that raises serious questions about the extent to which, and the ways in which, Assange’s activities themselves can be defined as journalism, and that sits in a broad conversation that we’re happening in all liberal democracies about journalism and what it amounts to in a digital age when pretty mush anybody with a keyboard can publish their views. So there’s that whole subset of freedom of speech which, in and of itself, is difficult and complicated and becoming more and more complicated by the nature of the online environment where any person with a keyboard can theoretically put things out into the airwaves - though of course Assange did more than that.

Then the bigger issue of course is free speech and here we also have, in my view, a really fundamental challenge that we’re seeing lots and lots of examples of in court cases, in the Assange events and so on, which is a complete overturning of what free speech means. So I think that the Assange incident is just one incident among many where the concept of free speech is being turned on its head. And what I mean by that is that free speech has a philosophical principle and also as a legal principle, was developed in order to protect public discourse around things that matter to democratic self-governance, and to protect that discourse from excessive intervention by government because we wanted to be careful to ensure that government didn’t want to over-censor us and overplay their hand and act in a tyrannical way.

And today, in so many areas, the concept of free speech has been stretched and distorted to apply to situations where it didn’t used to apply, and as a result, in my view, the whole concept of free speech has been fundamentally weakened. And I’ll give you a couple of examples. One is that commercial speech, which is what companies say publicly, used to be considered easily regulable, as distinct from political public discourse. In the contemporary environment we expect more from our companies. We expect our companies to have positions on LGBTQA+ rights, we expect them to have positions on climate change, and so that is kind of playing at the edges.

(33:04) But more importantly, there’s actually a current case going on in the US where there is a challenge to a proposal by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to impose rules requiring public companies to make disclosures about their environmental impact, eg their greenhouse gas metrics, and the challenge to that is ‘You can’t force companies to release this information. That’s a violation of their free speech rights.’

We’ve had a law in California invalidated by the courts because it required healthcare providers to disclose the availability of the services they provide including, if that service was available, abortion. and so the law was imply requiring providers to say what provided as a service and that got overturned on free speech grounds.

We have free speech being applied to all kinds of areas where it ought not to be applied. We have bakers baking a cake, or refusing to bake a cake, being charged under anti-discrimination law, and being told that you cannot refuse to bake a cake - that is providing a service to customers, if you have gay customers who come and want you to bake them a cake even though you have a personal belief that same sex couples shouldn’t get married, you’re not allowed to deny them the cake because that’s a act of overt discrimination. And we have the bakers and photographers and florists and all kinds of people mounting free speech challenges to that.

I’m sure you have already noticed that the 12+ years of Assange’s arbitrary detention (as determined by UNWGAD) and his 4+ years (so far) of total gagging (ie a total removal of free speech from a man presumed innocent) got reduced to “the Assange incident” in that tirade.

As to ensuring that governments don’t “over-censor” us, I didn’t notice the phrase “It’s okay if governments don’t do it too much” in the First Amendment of the US Constitution or Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Scott Stephens (34:30):

Was that free speech? That was more a freedom of conscience challenge wasn’t it?

Katharine Gelber (34:33):

It was a free speech and freedom of religion challenge. It was the two components. And so in this way I think free speech is being stretched in an unmanageable way so that anybody who wants to win something is thinking ‘Well, I’m going to try free speech. That’s a winner. There’s very little evidence that people who try the free speech argument, especially in the US, are going to fail. And so we failed on other kind of political attempts to mobilise and campaign and strategise so let’s try this one.’ And so it’s being stretched beyond its original conception, beyond its original purpose, and his is what I fear.

Waleed Aly asks (35:13)

"How do you apply that concern to the Assange case, because the free speech argument, the genesis of free speech, is to do with freedom from government intrusion and allied to that - and this is where the media becomes relevant - is the indispensable process in a democracy of people being free to say things and expose things that governments don't want said and exposed? It seems to me that if you are going to say there is a conceptual slide going on, the Assange case may not be the best example of that because it is squarely on the issue of government intervention to limit or control speech and the exposure of ..."

Both Stephens and Gelber jump in (35:57) "Except it's not!"

Katharine Gelber states (36:00):

"It's a stretch because Assange is saying that 'I can illegally obtain information, I can exercise no prudence or caution in what I choose to make public. I can put individuals at risk because I want to. I can ignore all of the principles of journalism. And then when they come after me, which I knew was going to happen, I'm going to say ‘How dare you come after me. I have free speech.’ ”

COUNTERPOINT - re fictitious “quote”

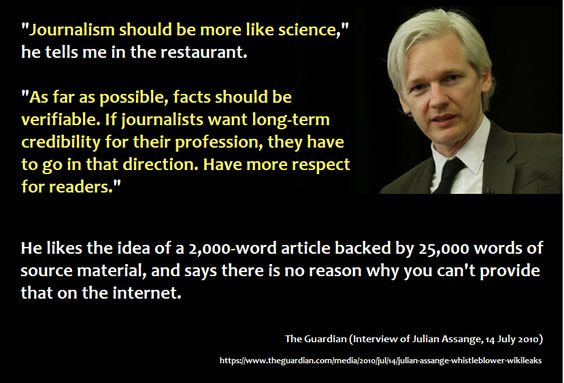

Waleed Aly fails to challenge any of the points in Gerber's fictitious, concocted (and defamatory) "quote" from Assange. It is not at all established that Assange obtained information illegally (there are many arguments to the contrary), and it has been well demonstrated that Assange exercised a great deal of caution (some of which was later undone by the outrageous publication of the password to unredacted files by the Guardian journalists) in relation to which files, and which names within those files, were exposed to the public.

The WikiLeaks principles of journalism are well documented, and have resulted in their website being the only publication in the world to have a 100% clean record in terms of never having published a document that was not what it was represented to be, and in its pristine original form.

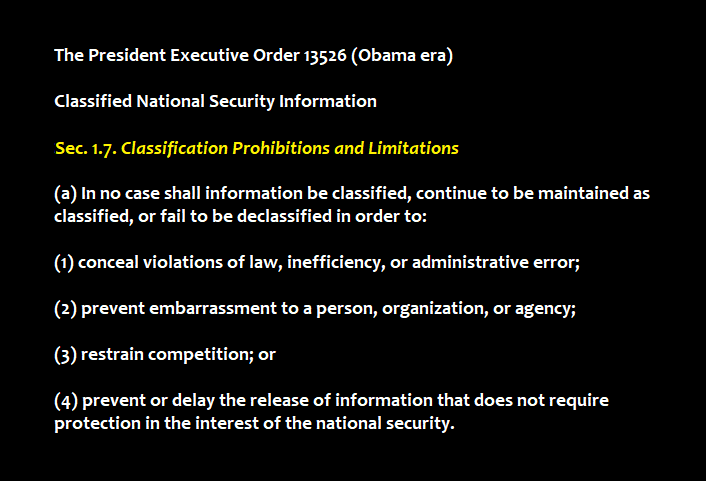

Further, this discussion does not address two important concerns re classified information:

There is no way to know the importance of hidden or “secret” information, and whether (or not) it is in the public interest for it to be exposed, without someone taking an independent look at the information. Hence the importance of whistleblowers, and the journalists and publishers who help them bring such documents to the attention of the public. It is not sufficient to simply say that one should take the world of the government as gospel - there are more than enough examples of government duplicity that predate WikiLeaks (surely no one has forgotten “Weapons of Mass Destruction” [WMDs] in Iraq).

The WikiLeaks material also raises the specter of War Crimes, which all those sworn to secrecy also have a constitutional duty, and a duty under international law, to report.

That war crimes (and other illegalities) cannot (legally) be hidden by rendering the relevant information classified was made explicit under President Obama’s Executive Order 13526:Many of the WikiLeaks disclosures are evidence of unmistakable war crimes - in particular the ‘Collateral Murder” video, which shows US military personnel shooting at the wounded, and riding roughshod over fallen bodies - both of which are explicit war crimes. Eminent US lawyer Marjorie Cohn discusses those war crimes at 13:15 in “The Prosecution of Julian Assange and the Threats to Freedom of the Press and Human Rights” (22 Oct 2021).

Of course the charges in the Assange indictment are for events that precede this executive order in time, but the order simply makes explicit rules of law which were previously implicit.

TRANSCRIPT CONTINUES:

Scott Stephens (36:49):

"One of the overblown claims that has been made by Assangists, or Assange supporters, is the fact that Julian Assange is being charged under the Espionage Act, again, creates precedent for journalists the world over - should they publish something that runs aground of American policy or whoever happens to be in the White House at that particular time - for them, in turn, to be extradited, and then charge with espionage.

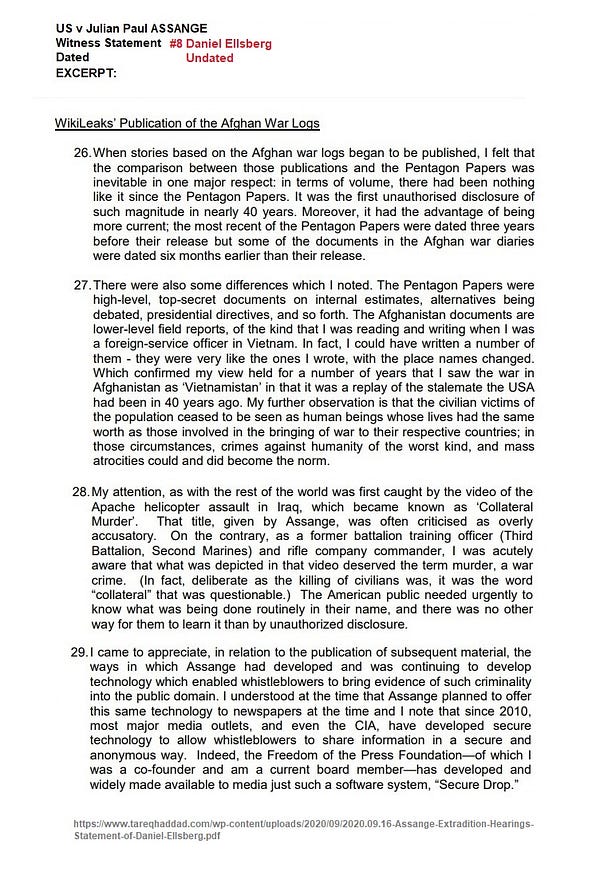

What’s really interesting to me is that a number of people have been drawing parallels between Daniel Ellsberg's disclosures of the Pentagon Papers - the 47 volume account of American foreign policy in Indo-China from the end of the second world war through to the Vietnam War, and what Julian Assange has done by publishing this sort of trove - the Afghan files and the Iraq files, the Diplomatic Cables and so on.

Of course Ellsberg himself has drawn such parallels, as witnessed by multiple quotes from him in this review, and his affidavit included as part of the defence argument in the extradition hearings. Ironically the case against Ellsberg himself was thrown out because the government attempted to spy on his psychiatrist’s records, a perfect parallel to the spying that was done on Assange in the Ecuadorian Embassy, including on his meetings with doctors and lawyers, allegedly on behalf of the CIA.

TRANSCRIPT CONTINUES

Scott Stephens (37:54):

What's really interesting, and we forget this, the publication pf the Pentagon Papers by the New York Times and Washington Post was in fact put on trial. It was put on trial and heard by the supreme Court in 1970 - NYT v US https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/403/713/ - . The US government tried to prevent the publication of reports stemming from the Pentagon Papers, and they tried to prosecute that under the grounds of the Espionage Act. The Supreme Court found entirely against them. And what was so interesting to me is they did so on two bases:

- (1) The Espionage Act assumes that the publication of information will do damage to the US and give support to, or give some kind of credence to, or strengthen position to foreign powers.

- (2) The other idea of the Espionage Act is that there is a kind of willfulness in the illegal procurement and the dissemination of that information in such a way that a degree of the intention or the forseeable intention of the gathering of information and its dissemination is that the US will be adversely affected."

Scott Stephens continues (39:10):

"What's so interesting is that the Supreme Court found two things.

(1) That the lies that were being told by the US government about the Vietnam War, these were not lies that were being told to other nations as part of American foreign policy, but these were lies - Hannah Arrendt described this beautifully, she said 'These were lies for domestic consumption'. These were lies as a way to build up or cover the US government's failings in the eyes of its own voters. Therefore, the Espionage Act found, did not apply. This was nothing that had to do with other nations,. It had to do squarely with how the American people would see its own government. Therefore the Espionage Act doesn't apply.

(2) The other thing - this is what I found so interesting, and this is why the connection that is often drawn between WikiLeaks and the Pentagon Papers just doesn't quite hold - one of the concurring opinions stated forcefully that the US had a very difficult balancing act to accomplish between

- (a) on the one hand protecting the First Amendment rights and the publication on the part of the press on the information that's in the public interest - these might include government secrets. On the other hand

- (b) the government's legitimate right, its legitimate interest, in keeping classified information secret. and so what the Supreme Court found was that the government should do everything that it can to keep information that it believes should be secret, secret. Now obviously that's going to be somewhat qualified by Freedom of Information requests [FOIAs], there are going to be whistleblowers which are protected, say like whistleblowing lawyers. There are ways of course for those cracks to be discovered and information that is intended to be kept secret to be allowed to come out into the light. That's sort of another story.But the other principle then is that if the press has a responsibility to bring things that are in the public interest into light, and if government has an interest in keeping certain things that ought to remain secret, secret, then the government should be permitted to

- (a) keep that information secret - even if that mean prosecuting people who might try to bring that information into the light, but

- (b) if that information is then made public, the press, given the particular protections that are accorded to the press and the standards of editorial responsibility, prudence and good judgment that go along with that, the press should be allowed to publish it.So that, I thought, is an astonishingly elegant solution here. Once things become public, provided that the proper editorial restrain, prudence, the rules that internally constrain the journalistic vocation are followed, the press' act of publishing ought to be permitted, but the government also ought to be given the ability to protect secrets that ought to remain secret.

What those who are so fervently advocating for Assange seem to be overlooking - are we really saying that states don't have an interest or shouldn't have a right to keep certain things secret. Are we really saying that they shouldn't be allowed to prosecute those who break in or conspire to illegally obtain information that ought to remain secret? It seems to me that the Supreme Court resolution, or the solution in 1971 - I think that is just about as good a solution as we are going to get, isn't it?

[This last phrase said with breathless excitement.]

Scott Stephens is on a roll (42:32):

“That means, just to put a bow on it, the 'free speech' argument is on the side of the press. The 'free speech' argument is not on the side of those who try to illegally obtain that information.”

Katharine Gelber chips in (42:43):

“Yes, or who publish it without exercising the editorial restraint and the prudence that is essential to that relationship. So the stretch here is Assange or Assange's team trying to rewrite what we define as journalism and therefore out to be subject to the most strenuous and robust free speech protections we can possibly get.

And that is what I disagree with. We can't allow that special protection to be extended to anybody with a keyboard no matter how they obtained the information, no matter what they want to release, and without exercising any editorial restraint, or prudence, or judgment.

If we do that then it becomes too broad and then we have lost that special protection which is so essential. It's not that I think protection isn't important. Quite to the contrary, I think that protection is absolutely essential to the right functioning of a democracy. We have to have it. And if we are to keep it we need to understand its parameters.”

Waleed Aly attempts (44:09) to move the conversation along with the question:

"Do we know for a fact whether any of these people were put in danger? Were any of the harmed, killed, or anything like that?"

COUNTERPOINT - Bob Carr (former Australian Foreign Minister) speaking to the European Parliament (14 November 2019) [EU video speech from 9:59:24, quote from 10:06:45] reported on the conclusion of the Australian Defence Taskforce on material released by Assange & WikiLeaks, at times quoting from their report directly:

"Let me quote: “The Task Force concluded that the leaked documents were tactical level operational reports containing ‘information that is now sufficiently aged that it poses minimal threat’.

The Task Force says that it was unlikely that AU or allied forces would be directly endangered by the leaks. The leaked documents did not contain ‘any significant details about operational incidents … beyond that already publicly released’.

The Task Force also investigated whether ‘WikiLeaks published any information that could put Afghan nations at risk of retribution for their work with Australian forces. The investigation found that no Afghans … were identifiable other than those who were with Australians openly, such as officials or community figures.’

So this internal review completely undermined comments by some commentators in Australia that ‘The disclosures risked endangering coalition troops and could bolster Taliban insurgent propaganda.’ […] It comprehensively rebuts the suggestion that lives were lost, or even put at risk."

TRANSCRIPT CONTINUES

Scott Stephens waxes lyrical (44:23):

“This is in fact, I think, a very important element. Again Assange’s supporters say that no evidence has been produced by the United States prosecutors to British courts that anybody was killed, injured, harmed, dot, dot, dot, as a result of Wikileaks indiscriminate leaking of unredacted information. What I think is conveniently left out of that however – it is true that the US prosecutors have not produced that information. To some extent however that is immaterial on two counts:

One is an astonishing amount of diplomatic, on the ground, collaborative work took place in the eighteen months following that data dump to try to get those who would have been adversely affected or killed out of harm’s way. So, to say that nobody was in fact killed and to say at the same that for eighteen months extraordinary lengths and extraordinary costs were undertaken in order to try and get said persons out of harm’s way, I am not sure if the first argument necessarily holds the water that it is meant to. In other words that this was a consequence less data dump and therefore no consequences should be broached.”

Note the judgmental term used here: “data dump”. Has Scott Stephens actually looked at the carefully categorised and indexed entries in the WikiLeaks files? There are also redactions in the records (clearly labelled). These are all signs of extensive and careful editing not at all deserving of the “data dump” label that legacy media people (so fond of their “unnamed sources) like to use.

Further, no evidence is proffered (or even alluded to) as to the “eighteen months extraordinary lengths and extraordinary costs” in mitigation mentioned here.

Scott Stephens continues (45:35):

“The other issue here, Waleed, and this where you might have to speak it, is the issue of the consequentiality of intention. Is the fact that Assange and Wikileaks was heedless – had no concern for the safety or wellbeing – I will just read you for instance what Assange said in response to some of the objections on the part of Guardian journalists about the danger to which informants would be subjected. This is from …… David Lee’s book on Wikileaks. “Well, they’re informants”. This is Assange. “Well, they’re informants so if they get killed, they have got it coming to them, they deserve it“. So whether or not someone did in fact get killed, does the heedlessness of the act itself, is that legally culpable even if no-one was in fact killed?”

COUNTERPOINT - Twitter MOMENT on this topic (12 Aug 2019)

- ”In Question - Did Julian Assange REALLY say that?”

“Many people have accused Julian Assange of being uncaring or unethical (or both) about people exposed in leaks. This stems from a story told by David Leigh (The Guardian) re the 2010 publication of the Afghan Diaries.

But did Julian REALLY say that?”

UPDATE:

[Sadly, in Feb 2024 Twitter (now X) disconnected existing Twitter MOMENTS from the tweets they contained (yet more destruction of the historic record). This discussion can still be followed by using the link to the connected THREAD:]

This Twitter MOMENT consists of a long THREAD of tweets taking the reader through the various (and varying) iterations of this piece of hearsay (with links to evidence), including - of course - the written affidavit of one of the journalists, John Goetz, at the dinner where the Guardian journalists allege the comment was made.

COUNTERPOINT - Craig Murray’s “Your Man in the Public Gallery: Assange Hearing Day 11” (re Extradition hearing 16 September 2020)

Yet another shocking example of abuse of court procedure unfolded on Wednesday. James Lewis QC for the prosecution had been permitted gratuitously to read to two previous witnesses with zero connection to this claim, an extract from a book by Luke Harding and David Leigh in which Harding claims that at a dinner at El Moro Restaurant Julian Assange had stated he did not care if US informants were killed, because they were traitors who deserved what was coming to them.

This morning giving evidence was John Goetz, now Chief Investigations Editor of NDR (German public TV), then of Der Spiegel. Goetz was one of the four people at that dinner. He was ready and willing to testify that Julian said no such thing and Luke Harding is (not unusually) lying. Goetz was not permitted by Judge Baraitser to testify on this point, even though two witnesses who were not present had previously been asked to testify on it.

Baraitser’s legal rationale was this. It was not in his written evidence statement (submitted before Lewis had raised the question with other witnesses) so Goetz was only permitted to contradict Lewis’s deliberate introduction of a lie if Lewis asked him. Lewis refused to ask the one witness who was actually present what had happened, because Lewis knew the lie he is propagating would be exposed.

This is my report of Lewis putting the alleged conversation to Clive Stafford Smith, who knew nothing about it:

Lewis then took Stafford Smith to a passage in the book “Wikileaks; Inside Julian Assange’s War on Secrecy”, in which Luke Harding stated that he and David Leigh were most concerned to protect the names of informants, but Julian Assange had stated that Afghan informants were traitors who merited retribution. “They were informants, so if they got killed they had it coming.” Lewis tried several times to draw Stafford Smith into this, but Stafford Smith repeatedly said he understood these alleged facts were under dispute and he had no personal knowledge.

This is my report of James Lewis putting the same quote to Prof Mark Feldstein, who had absolutely no connection to the event:

Lewis then read out again the same quote from the Leigh/Harding book he had put to Stafford Smith, stating that Julian Assange had said the Afghan informants would deserve their fate.

James Lewis QC knew that these witnesses had absolutely no connection to this conversation, and he put it to them purely to get the lie into the court record and into public discourse. James Lewis QC also knows that Goetz was present on the occasion described. The Harding book specifies the exact date and location of the dinner and that it included two German journalists, and Goetz was one of them.

It is plainly contrary to natural justice that a participant in an event introduced into the proceedings should not be allowed to tell the truth about it when those with no connection are, tendentiously, invited to. Whatever the rules of evidence may say, Baraitser and Lewis have here contrived between them a blatant abuse of process. It is a further example of the egregious injustices of this process.”

TRANSCRIPT CONTINUES

Waleed Aly (46:19):

“I don’t know the answer in law. I would suspect that this is an area where intention would necessarily matter. I think you come up with a policy position or a legal position based on the principles of whether or not certain things should be protected absolute and then that is that, right? And whether or not you were sensitive to something or heedless to something, if you have stepped over that line, you have stepped over that line. I think that is the way the law would have to work. It is not the same thing as making a moral judgement about it which is where our disagreement about the relevance of intention lies and the moral realm but in the legal realm, I am not entirely sure it would ….”

Katharine Gelber (46:52):

“Is it also the case here that you know under the rule of law you are supposed to be able to anticipate in advance whether something you are doing is illegal or not?”

Scott Stephens (47:00):

“Reckless endangerment!”

Katharine Gelber (47:01):

And so we can’t wait to find out whether people were killed as a result of what you did, to use that as a basis for deciding whether it was morally conscionable and whether it was legally appropriate. You have to be able to know in advance that if you are putting people at high risk then you are putting people at high risk.

Waleed Aly (47:17):

“Yeah, that is true for a court. I think that is right and for the formation of a law. I think what I am asking is whether or not we, as people who are not sitting in judgement in a court or whatever, but just looking at this from afar, can use that as a way of reflecting on whether or not the claim that this puts people in danger is a robust one. That’s all. So I think you are absolutely right Katharine in the way that you framed that, I think I am just asking a slightly different question or putting it in slightly different terms.”

COUNTERPOINT: Interview with John Shipton (29 June 2022) Narrative 100 by Robert Cibis “Julian, the Journalist” [YouTube now censored] [oval.media]

(at 4:32)

“Did he put people into danger?”“It's extraordinary. I characterise it as grotesque that the United States and NATO officials responsible for

- the destruction of seven and a half countries in 20 years,

- the murder of 5 million people,

- the creation of 36 million refugees

- (all of these figures are compiled by US institutions, Brown University for example)

that these people, swimming in blood, bringing death and destruction to human communities throughout the Middle East, stand and accuse Julian of endangering lives. It's just absolutely grotesque.”

[In this video John Shipton also comments on the documented conspiring of the UK’s Crown Prosecution Service (CPS, then headed by current UK Labour Party leader Keir Starmer) and their counterpart in Sweden to keep the Swedish “Enquiry” - from which no charges were ever laid) going over many years. He also comments on the Guardian leak of the password to the unredacted version of the US Diplomatic Cables.]

Scott Stephens (47:47): “Can I ask you a question Waleed?”

Waleed Aly: “Yeah sure.”

Scott Stephens (47:49):

“So, what’s wrong with this scenario. Let’s just say Assange is extradited. He is formally charged. He is placed on trial. Would I be wrong in thinking that will be one of the most heavily covered publicised, notable trials in the last two decades? Maybe more.”

Waleed Aly: (48:11) “No that’s right.”

No. That’s very probably wrong.

The UK already had 22 days of hearings at the District Court level, plus the High Court appeal, and very few of the legacy press attended. Mostly they relied on the AP and Reuters journalists who produced very blancmange reports with very little detail. The big newspapers clearly had no appetite for the issues being presented, many of which were harrowing, most of which were important for the future of our society. On the opening day, many reporters turned up to hear the prosecution open their case, but then did not stay to hear the defense, and did not return. There is no reason to believe things would be different in the US.

Craig Murray provided a very clear (if jaundiced) view of how the press behaved that first day:

“James Lewis QC made the opening statement for the prosecution. It consisted of two parts, both equally extraordinary. The first and longest part was truly remarkable for containing no legal argument, and for being addressed not to the magistrate but to the media. It is not just that it was obvious that is where his remarks were aimed, he actually stated on two occasions during his opening statement that he was addressing the media, once repeating a sentence and saying specifically that he was repeating it again because it was important that the media got it.

I am frankly astonished that Baraitser allowed this. It is completely out of order for a counsel to address remarks not to the court but to the media, and there simply could not be any clearer evidence that this is a political show trial and that Baraitser is complicit in that. I have not the slightest doubt that the defence would have been pulled up extremely quickly had they started addressing remarks to the media. Baraitser makes zero pretence of being anything other than in thrall to the Crown, and by extension to the US Government.

The points which Lewis wished the media to know were these: it is not true that mainstream outlets like the Guardian and New York Times are also threatened by the charges against Assange, because Assange was not charged with publishing the cables but only with publishing the names of informants, and with cultivating Manning and assisting him to attempt computer hacking. Only Assange had done these things, not mainstream outlets.

Lewis then proceeded to read out a series of articles from the mainstream media attacking Assange, as evidence that the media and Assange were not in the same boat. The entire opening hour consisted of the prosecution addressing the media, attempting to drive a clear wedge between the media and Wikileaks and thus aimed at reducing media support for Assange. It was a political address, not remotely a legal submission. At the same time, the prosecution had prepared reams of copies of this section of Lewis’ address, which were handed out to the media and given them electronically so they could cut and paste.

Following an adjournment, magistrate Baraitser questioned the prosecution on the veracity of some of these claims. In particular, the claim that newspapers were not in the same position because Assange was charged not with publication, but with “aiding and abetting” Chelsea Manning in getting the material, did not seem consistent with Lewis’ reading of the 1989 Official Secrets Act, which said that merely obtaining and publishing any government secret was an offence. Surely, Baraitser suggested, that meant that newspapers just publishing the Manning leaks would be guilty of an offence?

This appeared to catch Lewis entirely off guard. The last thing he had expected was any perspicacity from Baraitser, whose job was just to do what he said. Lewis hummed and hawed, put his glasses on and off several times, adjusted his microphone repeatedly and picked up a succession of pieces of paper from his brief, each of which appeared to surprise him by its contents, as he waved them haplessly in the air and said he really should have cited the Shayler case but couldn’t find it. It was liking watching Columbo with none of the charm and without the killer question at the end of the process.

Suddenly Lewis appeared to come to a decision. Yes, he said much more firmly. The 1989 Official Secrets Act had been introduced by the Thatcher Government after the Ponting Case, specifically to remove the public interest defence and to make unauthorised possession of an official secret a crime of strict liability – meaning no matter how you got it, publishing and even possessing made you guilty. Therefore, under the principle of dual criminality, Assange was liable for extradition whether or not he had aided and abetted Manning. Lewis then went on to add that any journalist and any publication that printed the official secret would therefore also be committing an offence, no matter how they had obtained it, and no matter if it did or did not name informants.

Lewis had thus just flat out contradicted his entire opening statement to the media stating that they need not worry as the Assange charges could never be applied to them. And he did so straight after the adjournment, immediately after his team had handed out copies of the argument he had now just completely contradicted. I cannot think it has often happened in court that a senior lawyer has proven himself so absolutely and so immediately to be an unmitigated and ill-motivated liar. This was undoubtedly the most breathtaking moment in today’s court hearing.

Yet remarkably I cannot find any mention anywhere in the mainstream media that this happened at all. What I can find, everywhere, is the mainstream media reporting, via cut and paste, Lewis’s first part of his statement on why the prosecution of Assange is not a threat to press freedom; but nobody seems to have reported that he totally abandoned his own argument five minutes later. Were the journalists too stupid to understand the exchanges?

The explanation is very simple. The clarification coming from a question Baraitser asked Lewis, there is no printed or electronic record of Lewis’ reply. His original statement was provided in cut and paste format to the media. His contradiction of it would require a journalist to listen to what was said in court, understand it and write it down. There is no significant percentage of mainstream media journalists who command that elementary ability nowadays. “Journalism” consists of cut and paste of approved sources only. Lewis could have stabbed Assange to death in the courtroom, and it would not be reported unless contained in a government press release.”

[From Craig Murray (25 February 2020)]

Despite the negligent behaviour of the legacy press, those actually interested in the issues being contested in this case got excellent service from the alternative press (despite the court making access for them as difficult as possible), via

- online tweet streams of everything said in the court room,

- detailed daily reports,

- access to the witness statements, and so on.

Much of this is collated in PART 4 of this series. But the general public, reliant on the legacy press, saw almost nothing of this.

Scott Stephens (48:12):

“All sorts of First Amendment considerations, all sorts of representations from media bodies, from civil rights activists. All sorts of representations will be made. The idea that it would be a “show trial” to my mind is unconscionable and certainly when one considers the lengths to which Prosecutions, Department of Prosecutions, the Defence Department in the United States has gone to, to be very, very careful about what in fact is on trial here and what is not.

Would it really be a terrible thing for the fuzziness that may well exist surrounding First Amendment free speech protections and the demands of transparency within an accountable democracy? Would it really be a terrible thing for that to go on trial?

And if the assurances that the US Prosecutors have given that they would have no objection to Julian Assange, should he be convicted, spending the extent of his sentence in Australia, I am just wondering how is that the heavens falling? How is that a seismic challenge to the freedom of press and the transparency of western democracy?

The option of a prisoner transferring to their country of citizenship to serve their sentence was not a “kindness” offered by the US as part of their assurances, but rather a standard arrangement. However all appeal options must have been exhausted before this could take place. If Assange’s case were to make its way to the Supreme Court, and a conviction to hold, another six years minimum would probably have passed. (Nils Melzer estimates a decade, see Ch13, p325.) That’s at least six years on top of the 12+ years he has already been arbitrarily detained. I imagine that would feel like a very hard rain falling to Julian Assange.

Waleed Aly (49:31):

“To ask me that question is tricky because you are making me mount an argument that I am not making. That is not a position I am making – I am not saying the heavens would fall in. I think, I can see my way to your position of saying you know that there is something beneficial to be gained from at least prosecuting that. Of going through that process.

Maybe the position that I come from, which is why it was my starting position, was a nervousness about this and it is a nervousness that isn’t settled by saying the media has a whole lot of interests that it will represent in this trial because the media’s interests are also going to be those of dealing with a competitor, and not just a competitor in media but a competitor in model and the court is going to have to weave their way through this.

So, whenever you talk about, you know, the legitimate interests of the state in protecting its assets etc, etc, it wouldn’t be hard for me to construct a scenario of perhaps a different government or a different war or a different effort the involves informants that is doing something that is so gravely unconscionable in another country. And I would argue that the Iraq war does fit that category. But you know other kinds of subterfuge and regime change.

If we were talking about someone who had released these documents about a government that we find far more distasteful, I don’t know, you want to say, who is unpopular at the moment – the Russian government, something like that, I think we would approach these principles in a very different direction. I think that is what I am perhaps reacting …”

Scott Stephens: “Strongly”

Waleed Aly (51:08):

“Perhaps strongly isn’t the right word, but I think what I am reacting to is the sense that so many of the presumptions here proceed on the basis of the goodness of the state and the legitimate interests of the state in these respects being so unimpeachable. “

Scott Stephens: “Interesting.”

Katharine Gelber: “And the …”

Waleed Aly: “That concerns me …”

Katharine Gelber (51:25):

“Yeah, I agree with that. And there is also another reason to be nervous about that trial that you outlined Scott and that is that we live in an age of alternative facts. We live in an age where huge numbers of people believe things that are evidently not true.

We live in an age where data, where facts matter less than they ought to for the good functioning of democratic institutions and this trial, if it goes ahead, as I agree one of the most widely covered trials, is likely to provide fodder for that particular problem. Which is a huge problem of course and there is no easy solution to it and I am not saying we should deny justice in some way because it feeds the machine but this is another reason to be nervous about that trial I think.”

Scott Stephens: “You mean even if there is a benefit in establishing precedent?”

Katharine Gelber: “Yes.”

Scott Stephens (52:21):

“There could be a profound detriment in that the trial itself would be so divisive that it deepens the already bitter dispute that kicked off this conversation?”

Katharine Gelber (52:32):

“And corrosive to those democratic institutions that are so essential for our ability to find our way out of the increasing government intervention against free speech. So, my overall view is that governments are overreaching on free speech. That governments are interfering in free speech far more than they should and the difference between the Pentagon Papers and today is we have had 911, we have had rafts and rafts of lawmaking in liberal democracies that significantly impinges on free speech.

So, I am not naïve about that, but I think there are reasons to be nervous for the robustness of our democratic institutions as a result of the saga - that is not just Julian Assange but the whole thing.”

Waleed Aly (53:21):

“In our informational landscape this is becoming an argument that we have evolved a society that is unworthy of the institutions that were designed to protect it.”

Katharine Gelber: [Laughing]

Waleed Aly: “That’s a good sequel to this show.”

Katharine Gelber: [Laughing]

Waleed Aly:

“And that will have to be a sequel because we are out of time. Katharine thank you so much.”

Final Commentary

It is true that Julian Assange knew what he was getting himself into, at least from early on. He had read the 7 Dec 2020 email (the date of his first arrest) from Fred Burton, VP of Intelligence at Stratfor - a CIA-linked ‘private intelligence agency‘ (for which hacked email archive Jeremy Hammond was sentenced in 2013 to 10 years in a US prison). It said:

“Pile on. Move him from country to country to face various charges for the next 25 years. But seize everything he and his family owns, to include every person linked to Wiki.”

It may surprise those who have read this far to find that I am in agreement with some of what what was said towards the end of this podcast about the virtue of finally having this case hammered out in the US Supreme Court.

If the UK ultimately declines to extradite Julian Assange he will be unable to travel outside the UK (of which he is not a citizen) without being at risk of the whole process starting up again. This is what happened to Lauri Love after his extradition was declined on health grounds.

There are only two ways to rid the world of this threat hanging over the head of Julian Assange and, by extension, the heads of all investigative journalists world-wide who do not allow themselves to be constrained by the mainstream Orwellian narrative.

If Julian’s case goes to the Supreme Court and the court make clear that this treatment of a journalist and publisher is ultra vires the First Amendment of the US constitution, that would create an important precedent.

First Amendment“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

Alternatively, the US government could withdraw the case against Julian Assange, acknowledging that he was wrongly indicted (with appropriate apology and compensation - as recommended by UNWGAD) while simultaneously repealing the Espionage Act.

However, neither is likely to occur. The second is unthinkable under current political conditions, while the first would require Julian Assange to survive extradition and imprisonment in the vile conditions of a US supermax prison for at least six years while the process played out. Given the state of his health (he already had a mini-stroke during the High Court appeal hearing), it is most unlikely he could survive that long.

This leaves us all in a terrible stalemate in current political conditions, which is not assisted by the ignorant and unfeeling remarks bandied about in the propaganda exercise the ABC and the three participants provided in this podcast.

Katharine Gelber said (above) that “we live in an age of alternative facts. We live in an age where huge numbers of people believe things that are evidently not true.” She was right - but it is not the “Assangists” who are making up ‘facts’ that are ‘evidently not true’.

In the unspeakably awful introductory part of the podcast Waleed Aly said “Today we are discussing a story that feels like it has been around forever … but I feel like it is one of those stories we have, as a public, discussed very badly for a very long time.” He was right about that. The conversation within and around the mainstream media has been appallingly ignorant and unhelpful. But this hour long podcast did not improve that situation. I hope the “conversation” with the podcast contained in this review has helped redress that somewhat.

Jonathan Cook said (26 March 2022):

“If we could discuss only two issues – those certain to have the most devastating implications for our future – they would be

climate breakdown and

the silencing of Julian Assange.

And yet, meaningful coverage of both is always crowded out by more pressing 'news.”

“If you don't understand why Assange makes that short list, it is because the media and political class have successfully obscured how his work threw open a window on corporate-military power and its destruction of our planet.

We need Assange, which is why he's being disappeared.”

What can we do to change that? We can resist the disappearance and persecution of Julian Assange. And we do that by searching out true facts and reliable commentators (not being persuaded by the half-baked and unsubstantiated opinions of ill-informed academics and pontificators) and by speaking up, and taking action.

As a long time supporter of Julian Assange, I have become aware that many of those new to the story of WikiLeaks and Julian Assange find it hard to get a picture of the enormity and multidimensionality of the abuse that has gone on here, and what that says about the current state of the world we live in.

My thanks to Dr Lilliana Corredor for her research assistance for this episode in this series.

You can find me on Twitter at La Fleur Productions.

The Assange and WikiLeaks series:

This is the ninth in a series of lengthy pieces that explore the history of Julian Assange and the WikiLeaks community via different themes: